The Problem

Verisign, a publicly traded U.S. company that provides Internet infrastructure and services, was granted exclusive management over the .com and .net generic top-level domains.

According to the Internet Watch Foundation’s 2020 report, 82% of all websites containing child sexual abuse material were registered on .com and .net domains.

While some other registrars and registries are disrupting domains associated with child sexual abuse material, Verisign fails to take meaningful action and instead inhibits attempts to protect children.

Verisign holds incredible power to help stem the growing epidemic of child sexual abuse. So, why won’t it step up?

Congress must act to hold Verisign accountable. Read more and take action!

Ways Verisign Inhibits Attempts to Protect Children

As a titan of Internet infrastructure, Verisign has a responsibility – and ability – to create safe online spaces. They must be held accountable for their inaction and poor policies that allow child sexual abuse to flourish on the .com and .net domains which they have been entrusted with to manage. These issues around technology are complex, so here is a summary of ways Verisign inhibits attempts to protect children:

VERISIGN DOES NOT ENFORCE ITS CONTRACTS WITH REGISTRARS WHO ALLOW CSAM TO FLOURISH. VERISIGN HAS THE POWER TO SHUT THEM DOWN.

Here is a copy of the contract Verisign has with each of the registrars selling .com or .net.

Verisign, since its purchase of Network Solution, has been granted exclusive management authority over .com and .net by the United States Department of Commerce and the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) since their creation, refuses to enforce contract terms with registrars who allow child sexual abuse material to proliferate on their platforms. If Verisign would do this even one time with just one registrar, it would cause a tectonic shift as then all registrars selling the .com and .net domains would improve their proactive efforts to stop CSAM. For example, given the extensive amount of evidence that Pornhub allows child sex abuse material to proliferate on its site, Verisign could (and should) enforce its contract and shut down Pornhub.com. As of right now, there’s really no financial incentive or business reason for the registrars to put resources into curbing CSAM without the pressure of the registry.

Verisign’s contracts with registrars also gives it the right to shut down secondary domains at the root if they are hosting illegal material such as child sexual abuse material. Verisign instead puts the onus completely on the registrars to do this and claims they couldn’t do it anyway because they don’t have a “Thick WHOIS.” This brings us to the second reason Verisign is part of the problem when it comes to child safety online.

VERISIGN REFUSES TO COLLECT THE NECESSARY INFORMATION FOR A SECURE AND SAFE INTERNET THROUGH A THICK WHOIS DESPITE REQUIREMENTS AND MANY YEARS TO DO SO.

As explained by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration: “The WHOIS databases are the internet’s white pages. Every entity, whether individual, business, organization or government, which registers domain names, must provide identifying and contact information. This information includes, but is not limited to, name, address, email, telephone number, and technical contacts. This data is managed by “registrars” and “registries.”

The importance of this data cannot be overstated. Having access to contacts for websites and domain names is essential for law enforcement, cybersecurity, and IP interests.”

Verisign is the ONLY registry in the entire Domain Name System of generic top-level domain names that does not operate a Thick WHOIS registration data directory.

For a decade, the Internet corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and the ICANN multi-stakeholder community have agreed on the substantial benefits of requiring all registries to hold Thick WHOIS data. ICANN ordered Verisign to implement a Thick WHOIS in 2014 and was given five years to do this. Verisign is now three years past the deadline for creating a Thick WHOIS.

Instead, Verisign continues to push for extensions while no apparent work has been done to move towards implementing a Thick WHOIS.

When it comes to curbing child sexual abuse material, because Verisign refuses to implement a Thick WHOIS, Verisign simply claims they don’t have the ability to give law enforcement the information needed or to shut off known secondary domains hosting CSAM because they don’t have access to that information. If they had a Thick WHOIS as is required, they would have that information.

By what can only be interpreted as deliberate dysfunction, Verisign is facilitating the exponentially increasing crime of child sex abuse material. In fact, the IWF named 2021 the worst year on record for online child sexual abuse. It’s not unreasonable to surmise that a Thin WHOISE has created a massive law enforcement gap that is being exploited by predators and pedophiles who explicitly register .com and .net domains knowing they will be more difficult to trace and therefore shut down.

The two issues highlighted above are highly concerning and pressure must be applied by the public and governments – including US Congress to correct.

VERISIGN HAS NOT IMPLEMENTED A ROBUST NOTIFIER PROGRAM TO PROVIDE TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN THE .COM TOP LEVEL DOMAIN. AFTER FOUR YEARS, IT APPEARS LITTLE PROGRESS HAS BEEN MADE.

Another reason NCOSE believes Verisign deserves a place on the Dirty Dozen List is because it has yet to implement a robust trusted notifier program, which seems to be a basic step towards improving child safety.

A “trusted notifier” is an entity with recognized authority and extensive expertise in the area in which it operates that would be able to accurately identify illegal material (read more about trusted notifier elements here).

Verisign promised to implement such a program in 2018 in connection with the execution of Amendment 35 to the Cooperative Agreement with ICANN. In February 2020,The National Center on Sexual Exploitation, together with five other organizations working for child safety including ECPAT-USA, Enough Is Enough, Childsafe.ai, Sanctuary for Families, and SPACE International, brought our concerns to Verisign. In a joint letter and in follow-up phone conversations, we urged Verisign to get it going immediately as two years had already passed.

Last year, we called out Verisign on the Dirty Dozen List for not having yet implemented a trusted notifier program for child safety groups. They did finally inform us, after we sent them two more letters in February and March of 2021, that they created a trusted notifier program with UK-based Internet Watch Foundation.

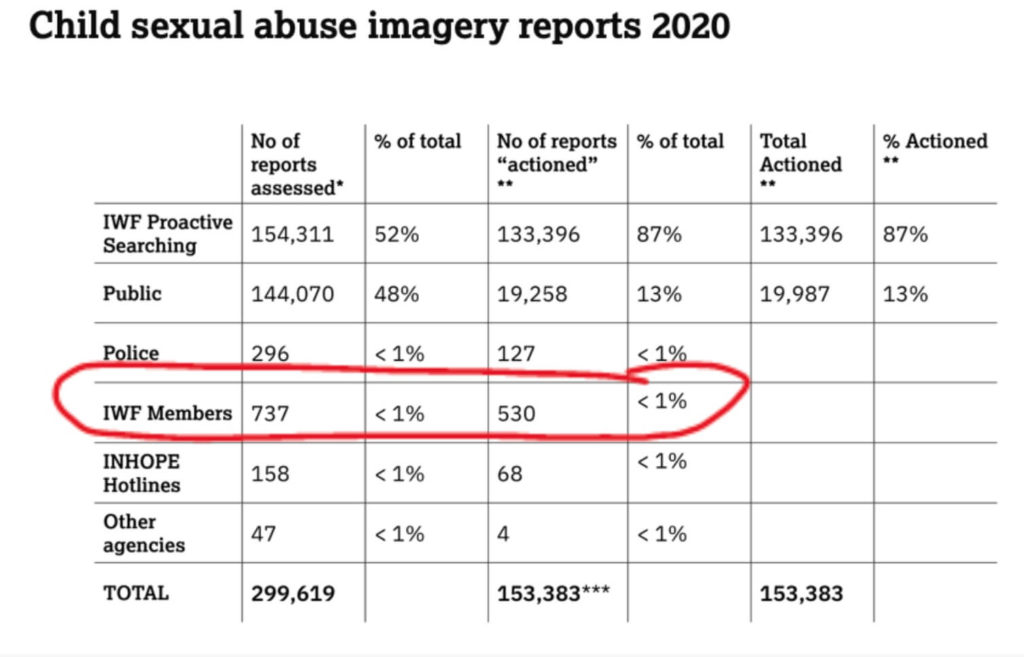

IWF is still listed as the only trusted notifier for CSAM on Verisign’s website. As a member of IWF, Verisign pays a fee of $105,893.73 (the highest possible) to have access to IWF’s innovative technology to keep their network and platforms clear of known CSAM. Verisign states on its website that under their relationship with the IWF, Verisign is “committed to taking action against every .com, and .net domain name reported to [them] by IWF as being used to host CSAM-related content.” This is a bold statement given that the IWF reported that 82% of the CSAM found on top level domains in 2020 were found on Verisign-managed .com and .net (98 -99% if you take out country code TLDs). And despite being given technology by IWF to proactively scan for CSAM, IWF members (which include most of the tech giants like Google, Meta, Amazon, etc.) reported less than 1% of the total CSAM reports in 2020. We don’t know if any came from Verisign.

Verisign also notes on its website that it has a “commitment as an Electronic Service Provider registered with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), to bring to NCMEC’s attention instances of the online exploitation of children.” In 2020, Verisign sent in 30 reports to NCMEC. Verisign explained to NCOSE in a letter that NCMEC’s number was inaccurate and that in fact they reported 520 domain names related to CSAM to NCMEC.

Let’s review some data:

- 5,590: number of domains containing child sex abuse images in 2020 (IWF)

- 520: number of domains Verisign says it reported to NCMEC in 2020

- 82%: percentage of domains hosting CSAM in 2020 that were .com and .net. (managed by Verisign)

- 98%-99% of gTLDs (so not including country codes) hosting CSAM in 2020 that were .com and .net

- .com and .net account for 57% of all TLDs worldwide, including country codes (as of 1/2022)

Something isn’t adding up here.

While we commend Verisign for finally starting to report to NCMEC in 2020 (again, only after NCOSE and allies demanded to understand Verisign’s negligence to do so earlier) the overall numbers seem incredibly small. Especially given the overall market share Verisign has over worldwide TLDs, and the astronomically high percentages of child sex abuse material found on .com and .net. Perhaps Verisign is reporting many more cases of CSAM. But neither has Verisign shared those with us or the public, nor is it reflected in any publicly available reports. Most corporations now have transparency reports as they want to ensure everybody knows there are doing everything they can to combat this egregious crime. Why doesn’t Verisign?

While Verisign has technically kept its promise to implement Amendment 35 to the Cooperative Agreement with ICANN to create a trusted notifier, instead of having just one private -entity trusted notifier that is benefiting financially from Verisign – perhaps Verisign should expand its relationships and be transparent about how it is fighting CSAM by sharing data.

See Our Requests For Improvement

WE REQUEST VERISIGN IMPLEMENT THE FOLLOWING IMPROVEMENTS:

- Verisign must comply with the ICANN mandate to implement a Thick WHOIS.

- Verisign must verify the identity and location of the domain registrant, screen for potential abuse of the domain, and audit a domain on such TLDs for such abuse on .com, .net (or other TLDs that Verisign manages or provides back-end registry services to).

- Verisign should, on a voluntary basis (i.e. absent a court order) help to disrupt domains on .com (or .net or other TLDs that Verisign manages) that are associated with child sexual abuse materials or human trafficking.

- Verisign should release a transparency report to show how many cases of CSAM it has removed or reported to any entity – public or private.

Research & FAQ's

What is a Registry vs a Registrar vs a Registrant?

A domain name registry is an organization that manages top-level domain names. Verisign is a registry. They create domain name extensions, set the rules for that domain name, and work with registrars to sell domain names to the public. Network Solutions and GoDaddy are popular registrars. A registrant is the person or company who registers a domain name.

Concern #1: Verisign does not enforce its contracts

Verisign does not enforce its contracts with registrars who allow CSAM to flourish. Verisign has the power to shut them down.

Verisign, who has had the ultimate authority over .com and .net since their creation, refuses to enforce contract terms with registrars who allow child sexual abuse material to proliferate on their platforms. If Verisign would do this even one time with just one registrar, it would cause a tectonic shift as then all registrars selling the .com and .net domains would improve their proactive efforts to stop CSAM. As of right now, there’s really no economic reason for the registrars (companies like GoDaddy or Network Solutions) to put resources into curbing CSAM.

Verisign’s contracts with registrars also gives it the right to shut down secondary domains at the root hosting child sexual abuse material. Verisign instead puts the onus completely on the registrars to do this and claims they couldn’t do it anyway because they don’t have a “Think WHOIS.” This brings us to the second reason Verisign is part of the problem when it comes to child safety online.

Concern #2: Verisign refuses to implement a Thick WHOIS

Verisign refuses to collect the necessary information for a secure and safe Internet through a Thick WHOIS despite requirements and many years to do so.

As explained by the NTIA: “The WHOIS databases are the internet’s white pages. Every entity, whether individual, business, organization or government, which registers domain names, must provide identifying and contact information. This information includes, but is not limited to, name, address, email, telephone number, and technical contacts. This data is managed by “registrars” and “registries.”

The importance of this data cannot be overstated. Having access to contacts for websites and domain names is essential for law enforcement, cybersecurity, and IP interests.”

Verisign is the ONLY registry in the entire Domain Name System of generic top level domain names that does not operate a Thick WHOIS registration data directory.

For a decade, ICANN and the ICANN multi-stakeholder community have agreed on the substantial benefits of requiring all registries to hold Thick WHOIS data. ICANN ordered Verisign to implement a Thick WHOIS in 2014 and was given five years to do this.

Verisign has still not implemented a Thick WHOIS and instead continues to push for extensions while it appears no work has been done to move towards implementing a Thick WHOIS.

When it comes to curbing child sexual abuse material, because Verisign refuses to implement a Thick WHOIS, Verisign simply claims they don’t have the ability to give law enforcement the information needed or to shut off known secondary domains hosting CSAM because they don’t have access to that information. If they had a Thick WHOIS as is mandated, they would have that information.

What is Thick vs. Thin WHOIS?

ICANN specifies what information must be collected with respect to domain names in its Registry Agreement (RA) with accredited registries and its Registrar Accreditation Agreement (RAA) with registrars. The registration data is commonly referred to as WHOIS data. Thick WHOIS data refers to both information associated with the domain name itself as well the registrant (the person or entity who purchased the particular domain name) including detailed contact information about the registrant. Thin WHOIS data, on the other hand, is only the more limited data associated with the domain name itself, such as the registrar that sold the particular domain name and the creation and expiration date of the domain name.

What are the advantages for Registries to have Thick WHOIS?

For nearly a decade, ICANN and the ICANN multistakeholder community have agreed on the substantial benefits of requiring all registries to hold Thick WHOIS data. These include centralization of data (e.g., usually there are multiple registrars that sell and register domain names in any particular top level domain, such as .com or .net), data preservation, and consistency in data collection and display. The 2013 Final Report on Thick WHOIS Policy Development Process (Report) noted:

“From a technical perspective, a thick Whois model provides a central repository for a given registry whereas a thin Whois model is a decentralized repository. Historically, the centralized databases of thick Whois registries are operated under a single administrator that sets conventions and standards for submission and display, archival/restoration and security have proven easier to manage. . . . A thick Whois model also offers attractive archival and restoration properties. If a registrar were to go out of business or experience long-term technical failures rendering them unable to provide service, registries maintaining thick Whois have all the registrant information at hand and could transfer the registrations to a different (or temporary) registrar so that registrants could continue to manage their domain names. A thick Whois model also reduces the degree of variability in display formats. Furthermore, a thick registry is better positioned to take measures to analyze and improve data quality since it has all the data at hand.”

Thus the Report endorsed a previous working group’s conclusion to “recommend requiring thick Whois across incumbent registries – in order to improve security, stability and reliability[.]”

What Registry doesn’t have Thick WHOIS?

The 2013 Final Report on Thick WHOIS Policy Development Process noted that as of that time, only the registry for .com, .net, and .jobs operated as a thin WHOIS registry. All other legacy generic top-level domain name registries already were operating under Thick WHOIS. Verisign is the registry for .com, .net and .jobs. Therefore, Verisign is the ONLY registry in the entire Domain Name System of generic top level domain names that does not operate a Thick WHOIS registration data directory.

When the new generic top-level domain names were rolled out to the marketplace starting in 2013, all the registries for such new generic top-level domain names were required under their operative RAs to operate with Thick WHOIS registration data directories.

Doesn’t the GDPR prevent Verisign from implementing Thick WHOIS?

Verisign has argued that the GDPR (EU General Data Protection Regulation) is preventing it from implementing Thick WHOIS. But given that every single other registry for generic top level domain names, whether they be U.S. based registries, such as Public Interest Registry for .org and Neustar for .biz, or foreign registries have adopted Thick WHOIS and continue to comply with its requirements, this argument lacks merit.

But, has there been enough time for Verisign to transition to a Thick WHOIS?

ICANN began working on policy towards a Thick WHOIS 2011. ICANN formerly adopted the policy and instructed Verisign to transition to a Thick WHOIS in Feb 2014. Despite the fact that from the time the Board adopted the policy recommendations over four years were granted for the transition to Thick WHOIS for new domain name registrations and five years granted for the transition of all existing domain name registrations from Thin to Thick, Verisign still to this day has not implemented Thick WHOIS. And it is fairly clear that Verisign never intends to do so.

More details:

Timeline for Thick WHOIS ICANN Consensus Policy

As far back as 2011, ICANN began working towards policy that would potentially require all registries for all generic top level domains to operate under Thick WHOIS. In May 2011 an ICANN Working Group recommended that an analysis be conducted on the requirement of Thick WHOIS for all incumbent generic top level domains, such as .com and .net. Following completion of the study, in March 2012 the GNSO Council initiated a Policy Development Process on Thick WHOIS. A Thick WHOIS Working Group was formed and published its initial report for public comments in June 2013. Following review of the public comments, the Working Group issued its final report in October 2013. The leading policy recommendation from that final report, which was backed by full consensus of the Working Group, was as follows:

“The provision of thick Whois services, with a consistent labelling and display as per the model outlined in specification 3 of the 2013 RAA, should become a requirement for all gTLD registries, both existing and future.”

In October 2013 the GNSO Council voted to adopt the Thick WHOIS final report recommendations and recommended to the ICANN Board of Directors that it approve them for implementation. In February 2014 the ICANN Board voted to adopt the Thick WHOIS policy recommendations, including the transition of .com, .net and .job from thin to Thick WHOIS, and instructed ICANN org as follows:

GNSO

“The Board directs the President and CEO to develop and execute on an implementation plan for the

Thick Whois Policy consistent with the guidance provided by the

Work then proceeded for over two years via the implementation review team and in October 2016 policy implementation dates were mandated as follows:

All new domain name registrations for legacy thin WHOIS generic top level domains must be submitted as Thick starting as of 1 May 2018 at the latest.

All registration data for existing domain names on legacy thin WHOIS domains must have been migrated from Thin to Thick by 1 February 2019 at the latest.

Delay of Thick Whois Implementation

Despite the fact that from the time the Board adopted the policy recommendations over four years were granted for the transition to Thick WHOIS for new domain name registrations and five years granted for the transition of all existing domain name registrations from Thin to Thick, Verisign still to this day has not implemented Thick WHOIS. And it is fairly clear that Verisign never intends to do so.

In October 2017, the ICANN Board granted a six month extension for the transition to Thick WHOIS for new domain names in the .com, .net and .jobs domains to October 2018 and an extension for existing registrations to July 2019. In April 2018, Verisign requested a further one year extension for implementation and in May 2018 the Board passed a resolution extending the date to complete the transition from Thin to Thick WHOIS for .com, .net and .jobs to January 2020. Two further extensions were requested by Verisign to the Board in September 2018 and in February 2019; and in both instances the Board granted further extensions. Then in July 2019 Verisign once again requested another one year extension.

In November 2019, the ICANN Board passed a resolution addressing the situation. The Board noted that “this is the fifth deferral of the compliance enforcement of the Thick WHOIS Transition Policy.” Instead of granting a further time extension, the Board gave the President and CEO of ICANN authority to defer compliance until a group of conditions have all been satisfied concerning the implementation of the Expedited Policy Development Process related to WHOIS and the GDPR.1 Despite the fact that every other registry of generic top level domain names other than Verisign currently operates a Thick WHOIS, Verisign has been given a seemingly indefinite pass from implementing this critical policy that worked its way through the ICANN multistakeholder (and multi-year) consensus policy process.

Critical Date Summary:

- October 2013: Thick WHOIS policy Working Group issues Final Report

- October 2013: GNSO Council approves Final Report recommendations and recommends Board adoption

- February 2014: ICANN Board adopts recommendations and directs policy implementation

- October 2016: Proposed Policy Implementation issued for transition to Thick WHOIS for .com, .net and .jobs setting forth deadlines of May 2018 and February 2019

- October 2017: ICANN Board grants a 6 month extension of deadlines

- May 2018: ICANN Board in response to Verisign request grants a second 6 month extension of deadlines

- October 2018: ICANN Board in response to Verisign request grants a third 6 month extension of deadlines

- March 2019: ICANN Board in response to Verisign request grants a fourth 6 month extension of deadlines

- November 2019: ICANN Board in response to Verisign requests grants a fifth deferral of Thick WHOIS

Concern #3: Verisign still has not implemented a trusted notifier program.

Another reason NCOSE believes Verisign deserves a place on the Dirty Dozen List is because it has yet to implement a robust trusted notifier program, which seems to be a basic step towards improving child safety.

A “trusted notifier” is an entity with recognized authority and extensive expertise in the area in which it operates that would be able to accurately identify illegal material (read more about trusted notifier elements here).

Verisign promised to implement such a program in 2018 in connection with the execution of Amendment 35 to the Cooperative Agreement with ICANN. In February 2020,The National Center on Sexual Exploitation, together with five other organizations working for child safety including ECPAT-USA, Enough Is Enough, Childsafe.ai, Sanctuary for Families, and SPACE International, brought our concerns to Verisign. In a joint letter and in follow-up phone conversations, we urged Verisign to get it going immediately as two years had already passed.

Last year, we called out Verisign on the Dirty Dozen List for not having yet implemented a trusted notifier program for child safety groups. They did finally inform us, after we sent them two more letters in February and March of 2021, that they created a trusted notifier program with UK-based Internet Watch Foundation.

IWF is still listed as the only trusted notifier for CSAM on Verisign’s website. As a member of IWF, Verisign pays a fee of $105,893.73 (the highest possible) to have access to IWF’s innovative technology to keep their network and platforms clear of known CSAM. Verisign states on its website that under their relationship with the IWF, Verisign is “committed to taking action against every .com, and .net domain name reported to [them] by IWF as being used to host CSAM-related content.” This is a bold statement given that the IWF reported that 82% of the CSAM found on top level domains in 2020 were found on Verisign-managed .com and .net (98 -99% if you take out country code TLDs). And despite being given technology by IWF to proactively scan for CSAM, IWF members (which include most of the tech giants like Google, Meta, Amazon, etc.) reported less than 1% of the total CSAM reports in 2020. We don’t know if any came from Verisign.

Verisign also notes on its website that it has a “commitment as an Electronic Service Provider registered with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), to bring to NCMEC’s attention instances of the online exploitation of children.” In 2020, Verisign sent in 30 reports to NCMEC. Verisign explained to NCOSE in a letter that NCMEC’s number was inaccurate and that in fact they reported 520 domain names related to CSAM to NCMEC.

Let’s review some data:

- 5,590: number of domains containing child sex abuse images in 2020 (IWF)

- 520: number of domains Verisign says it reported to NCMEC in 2020

- 82%: percentage of domains hosting CSAM in 2020 that were .com and .net. (managed by Verisign)

- 98%-99% of gTLDs (so not including country codes) hosting CSAM in 2020 that were .com and .net

- .com and .net account for 57% of all TLDs worldwide, including country codes (as of 1/2022)

Something isn’t adding up here.

While we commend Verisign for finally starting to report to NCMEC in 2020 (again, only after NCOSE and allies demanded to understand Verisign’s negligence to do so earlier) the overall numbers seem incredibly small. Especially given the overall market share Verisign has over worldwide TLDs, and the astronomically high percentages of child sex abuse material found on .com and .net. Perhaps Verisign is reporting many more cases of CSAM. But neither has Verisign shared those with us or the public, nor is it reflected in any publicly available reports. Most corporations now have transparency reports as they want to ensure everybody knows there are doing everything they can to combat this egregious crime. Why doesn’t Verisign?

While Verisign has technically kept its promise to implement Amendment 35 to the Cooperative Agreement with ICANN to create a trusted notifier, instead of having just one private -entity trusted notifier that is benefiting financially from Verisign – perhaps Verisign should expand its relationships and be transparent about how it is fighting CSAM by sharing data.

Note: Verisign invited NCOSE to serve as a trusted notifier after we placed them on the 2021 Dirty Dozen List. However, this type of reporting is outside of NCOSE’s scope. We also decided to pause engagement with Verisign until we saw evidence of a good faith effort to enforce their contracts and move toward a Thick WHOIS: as relying on other (much smaller and less-resourced) entities to inform them of abuses when they could proactively be stemming the tide of CSAM seemed unproductive.