“Abuse is only increasing online, even though technology companies have more money and data than ever … That is why this year for the Dirty Dozen List, instead of focusing on 12 mainstream companies, we are focusing on ONE call to action: Repeal Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.” ~Haley McNamara, NCOSE Senior Vice President of Strategic Initiatives and Programs

In a special episode of the Ending Sexploitation Podcast, host Haley McNamara sits down with Dani Pinter, Senior Vice President and Director of the NCOSE Law Center, to discuss why, this year, NCOSE’s annual Dirty Dozen List campaign is taking a different approach.

The importance of this new approach is poignantly illustrated in the story of John Doe:

At 15 years old, John Doe downloaded and created an account on the 18+ dating app, Grindr. He was lonely, and often bullied at school for being gay and being on the spectrum. He thought he could find some companionship on Grindr.

Despite him being younger than the platform’s professed age limit, there was no meaningful age verification process in place. All he had to do was check a box to claim that he was over 18.

Almost immediately upon downloading the app, Grindr matched John with four adult male strangers. When he met up with the men in person, they raped him several times.

When John and his family filed a lawsuit against Grindr for facilitating this child sexual abuse, the court dismissed the case because of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act—a perplexing law which was intended to protect children, but instead became the greatest threat to their safety.

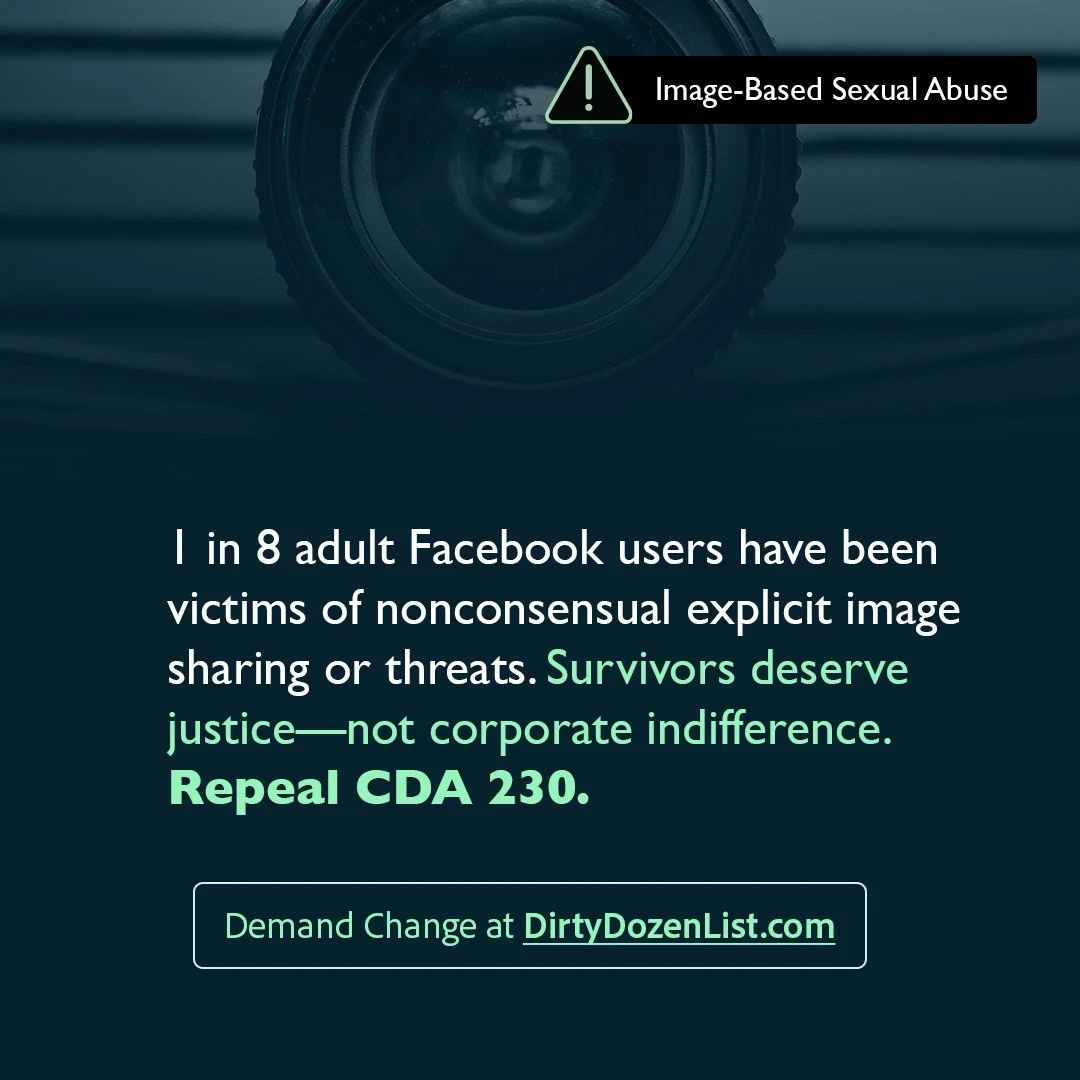

John Doe’s case is one of 12 survivor stories highlighted for the 2025 Dirty Dozen List. While previous iterations of the List have called out 12 companies facilitating sexual exploitation (often tech companies), this year we highlight 12 stories that expose the root cause of tech companies’ heinous behavior.

That root cause is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

Section 230 has effectively provided Big Tech with a massive shield that deflects any accountability they should face for malicious conduct that their platforms facilitate. And as the digital universe expands, online exploitation will continue to worsen with this law in place.

The Irony of Section 230: Written to Protect Children, Interpreted to Exploit Them

Pinter describes a brief history surrounding Section 230, which was ironically created to protect children, but has had the opposite effect:

“The irony is, it’s called the Communications Decency Act, because Congress was moved to actually account for making kids safe online. Already in 1996 [when the law was enacted], Congress was hearing from constituents that kids are being exposed to explicit content, being attacked, contacted by adults in chat rooms. So, Congress was actually taking action then at the very beginning of the Internet.”

So, what happened? How did we get to this point, where tech companies have turned this law on its head and used it for their own financial gain? Pinter explains a New York court case that derailed Section 230 from its original intentions and led us to where we are today.

“At that time, there had just been a case in New York that held a website accountable for defamation. A third-party user posted something on the website, and the website was held accountable for that because it was moderating posts.”

Since the website was moderating posts, the courts ruled that it “should have known” about the defamatory content, and therefore was liable. Whereas if they hadn’t been moderating posts, there wouldn’t have been an argument that they “should have known.”

The tech company in this case argued that if the court ruled that website can be held liable for defamation then, “every platform will either be sued because of all the bad actors on their site, or they won’t moderate because they’ll be afraid that will make them liable or they just won’t exist. It won’t even be worth going into business because of this law,” as Pinter puts it.

As a result of this, Congress tried to amend the law to promote good digital behavior.

“It’s actually called the Good Samaritan provision and it was meant, ironically, to incentivize platforms to moderate, to be good digital Samaritans, and in exchange, they would be immune from liability. And in a nutshell, it says platforms will not be treated as the publishers. That seems very common sense, but unfortunately, the way that courts have interpreted that over the past 20 years has been way broader even than Congress intended. It’s turned into essentially blanket immunity for any website, any web platform, for anything that a third party does. But it even gets interpreted beyond what a third party does to be anything their platform does that facilitates third party content,” said Pinter.

For example, Pinter explains how Grindr matching John Doe with adult predators went far beyond simple “third party content”—yet the company was still protected under Section 230.

“The Ninth Circuit found that even Grindr’s own tool which matched people, that ended up matching this adult predator with a child—I mean, Grindr designed that tool. That’s not something third parties did. Of course, third parties are ultimately matched. But Grindr’s own tool was immunized.”

In short, when children are sexually exploited on tech platforms, Section 230 protects the company from liability even when they are clearly taking an active role in contributing to the exploitation, and even when they could easily have prevented the exploitation but didn’t.

The Scope of Harm Caused by Section 230

The lawless Internet that Section 230 creates has made online spaces the most common places where sexual exploitation occurs. And this especially affects today’s children, as so many of them have unrestricted Internet access, making them vulnerable to predators.

While discussing Section 230 with Pinter, McNamara cites research from Thorn that found more than 1 in 4 minors (28%) reported having a sexual interaction with someone they believed to be an adult.

This plethora of child sexual exploitation is a direct result of dangerous product design and lackadaisical moderation on the part of media platforms. And that in turn is a direct result of Section 230.

Without liability, there is simply no incentive for tech companies to make their platforms safer. And so, exploitation flourishes.

Now is the Time to Take Action

Despite the origins of Section 230 being well-intentioned, it has been grossly misinterpreted over the past 30 years, which is why we are left with no other option than to call for its end. We have given tech companies enough time to come to the table to make reforms. Instead, they have continued to use Section 230 as a cop-out to continue profiting from exploitation.

“Tech companies are not in the business of being good people. They are in the business of making money,” said Pinter.

Pinter and McNamara discussed that with the growing public awareness surrounding Section 230 comes growing bipartisan support for repealing it. Members of Congress have held hearings, questioning survivors and experts on online exploitation, including one earlier this year. Our legislators are clearly paying attention, but conversations about ending Section 230 are not good enough. Pinter says it will take all of us to get them to push it past the finish line:

“There is a political will here, which is incredible to think about, because tens of millions of lobbying dollars [are] going into Congress’s pocket and yet, Congress is upset. When they say things like this publicly [speaking out against Section 230], they’re asking their constituents to back them up. They’re asking the public to back them up. So, this is such a unique opportunity.”

Listen to this episode of the Ending Sexploitation Podcast to hear more from Pinter and McNamara’s conversation.